Coffee is often seen today as a productivity booster or a cozy beverage, but during the Age of Enlightenment, it was much more than that. It became a symbol of reason, intellectual curiosity, and modern thinking. As Europe shifted away from superstition and absolutism and toward science and democracy, coffee helped fuel not only bodies—but minds.

This article explores how coffee, and the coffeehouse culture it nurtured, played a crucial role in shaping the Enlightenment era. From philosophers and scientists to revolutionaries and reformers, many of the great minds of the time were powered by the humble coffee bean.

Before coffee gained popularity in Europe, the most common daily beverages were alcohol-based: beer, wine, and ale were consumed even during breakfast. Water was often unsafe, and alcohol offered a safer alternative.

Enter coffee—a non-alcoholic, stimulating beverage that promoted clarity of thought instead of dullness. It was seen as a modern drink for a modern age. Suddenly, people were meeting in places where sober minds could think critically, debate ideas, and explore new possibilities.

This shift had profound consequences. Coffee wasn’t just a drink; it was a catalyst for rational discourse.

Coffeehouses in 17th and 18th-century Europe became intellectual salons—public places where men (and eventually women) of all social classes could discuss science, literature, philosophy, and politics.

In England, France, Germany, and Austria, these venues became known as “penny universities” because for the cost of a cup of coffee, one could access an atmosphere of learning and exchange.

Major Enlightenment figures like Voltaire, Diderot, Rousseau, and Kant frequented coffeehouses. Many newspapers, scientific journals, and revolutionary pamphlets were born from these café conversations.

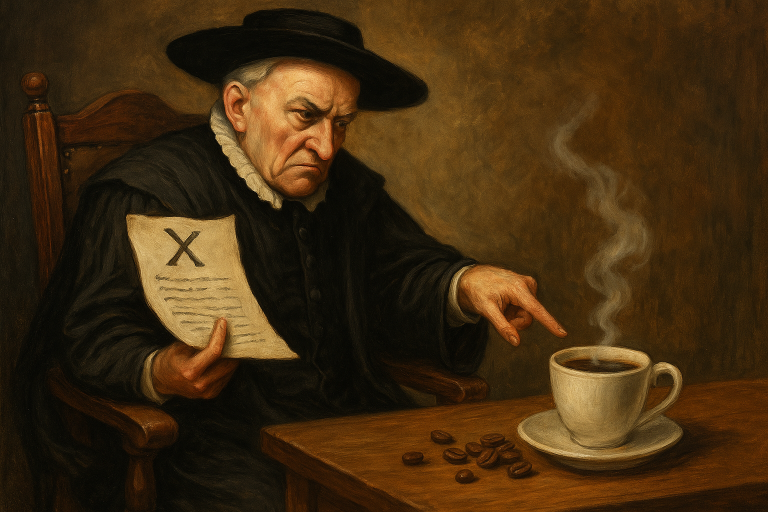

The Enlightenment emphasized logic, observation, and reason—values that were in direct contrast with the mystical and religious dominance of earlier centuries. Coffee was aligned with this worldview.

Unlike alcohol, coffee enhanced mental clarity, extended attention span, and promoted wakefulness—all essential for reading, writing, and debating. As such, it became associated with rationalism and intellectual superiority.

Writers and thinkers praised coffee for its ability to stimulate thought. Voltaire reportedly drank dozens of cups a day, believing it helped him write more effectively. Benjamin Franklin, one of the American Enlightenment’s key figures, was also a known coffeehouse regular.

German philosopher Jürgen Habermas later coined the term “public sphere” to describe the way people gathered to discuss ideas, critique government, and debate reforms. Coffeehouses were central to this concept.

In an age before social media or mass media, coffeehouses were where public opinion was formed. Citizens exchanged ideas and read newspapers aloud. News traveled faster through coffeehouses than through official channels, giving the public more autonomy and influence.

This rise of public discourse played a key role in revolutionary thinking—from the American Revolution to the French.

The Enlightenment was also the age of science, and coffee played a direct role in the culture of experimentation. Coffeehouses became unofficial laboratories of thought.

Scientific clubs and societies often met in cafés, where they exchanged data, discussed findings, and debated theories. In London, the Royal Society—the epicenter of scientific advancement—had close ties to local coffeehouses.

Astronomers, physicians, and chemists embraced coffee not just as a beverage, but as part of a scientific lifestyle.

The explosion of printed materials in the Enlightenment—books, pamphlets, essays, and newspapers—was tightly linked to coffee consumption.

Coffeehouses often had reading materials available to patrons. Some cafés developed their own newsletters, and many authors published essays that were first debated in coffeehouses. These venues helped popularize literacy and encouraged the idea that knowledge should be accessible to all.

The spread of ideas—especially controversial ones—was accelerated by the café network, often ahead of government censorship.

While coffeehouses were revolutionary spaces, they were not always inclusive. In many cities, women were excluded from public coffeehouses and had to form their own intellectual salons or participate in private gatherings.

However, this began to change over time, especially in France, where salon culture became an essential part of Enlightenment intellectual life. Women like Madame Geoffrin hosted gatherings where leading philosophers discussed science, art, and politics over coffee and wine.

Coffee became a bridge between public and private intellectual life, helping shape gender roles within the Enlightenment.

The connection between coffee and revolution is well documented. In America, coffee drinking spiked after the Boston Tea Party, as colonists rejected British tea in favor of coffee as a patriotic statement.

In France, revolutionary ideas were spread through cafés in Paris. Some of the most important moments leading up to the French Revolution were born over cups of coffee in places like Café de Foy.

Coffee was seen as the drink of the rational, rebellious thinker—a symbol of freedom from aristocratic decadence and religious dogma.

Coffee also symbolized a broader cultural shift: the move from a mystical worldview to a modern one. Whereas wine and ale were tied to ancient rituals and religious sacraments, coffee was secular, forward-looking, and utilitarian.

It became the drink of progress, embraced by those who saw the world not as it had been, but as it could be. Coffee helped usher in an age where evidence, logic, and debate took precedence over tradition and authority.

Today, many of the Enlightenment’s values still live on in coffee culture. Whether it’s writing in a café, studying with a coffee in hand, or debating politics over a latte, the ritual of coffee and conversation remains intact.

Coffee continues to represent freedom of thought, creativity, and the pursuit of knowledge—all pillars of Enlightenment philosophy.

Coffee helped define one of the most important intellectual eras in human history. It was more than just a drink; it was a symbol of transformation. From the seed planted in African soil to the minds it fueled in European cities, coffee became the elixir of the Enlightenment.

So the next time you sip your favorite brew, remember—you’re not just enjoying a warm beverage. You’re partaking in a centuries-old ritual that once powered revolutions, discoveries, and the very idea of modern thought.

Gabriel Rodrigues é especialista em finanças pessoais e escritor, com ampla experiência em economia, planejamento financeiro e gestão de recursos. Apaixonado por ajudar as pessoas a alcançarem sua saúde financeira, ele explora temas variados, desde investimentos até estratégias de poupança. Quando não está escrevendo, você pode encontrá-lo estudando novas tendências financeiras e oferecendo consultoria para quem busca melhorar sua relação com o dinheiro.